Maps have long been sources of fascination for people. In a recent post, we explored a broad range of map-making technologies, including LiDAR, a critical component of the ARway platform. In this post, we are going to scroll back a bit to understand how we got here and to consider the history and evolution of maps as objects and tools. We’ll also delve into how new technologies have allowed deeper levels of engagement, especially for mapping complex indoor spaces to improve the overall experience.

A two-dimensional representation of three-dimensional space has been a challenge since the dawn of time. The very earliest map, the Bronze Age Saint-Belec Slab (mentioned in the LiDAR post), was actually three-dimensional itself. This map – like other ancient and pre-modern ones – was not intended for navigation, but instead was to represent a space symbolically. In the case of the Saint-Belec Slab, scientists recently determined that it represents an area along the River Odet in Brittany. Amazing, yes, but at 5’ by 6.5’, not exactly portable!

Let’s look at a few of the other major milestones in the history of maps:

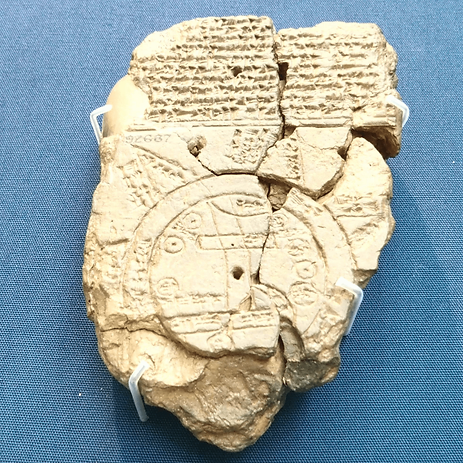

Mesopotamia, 700-500 BCE – a clay tablet showing Babylon at the center of the world. More detailed than the Slab, but still not a navigational tool. It served more to understand the relationship between spaces and to orient users as to their place in the world.

The Babylonian map of the world. Late Babylonian, 700—500 BC.

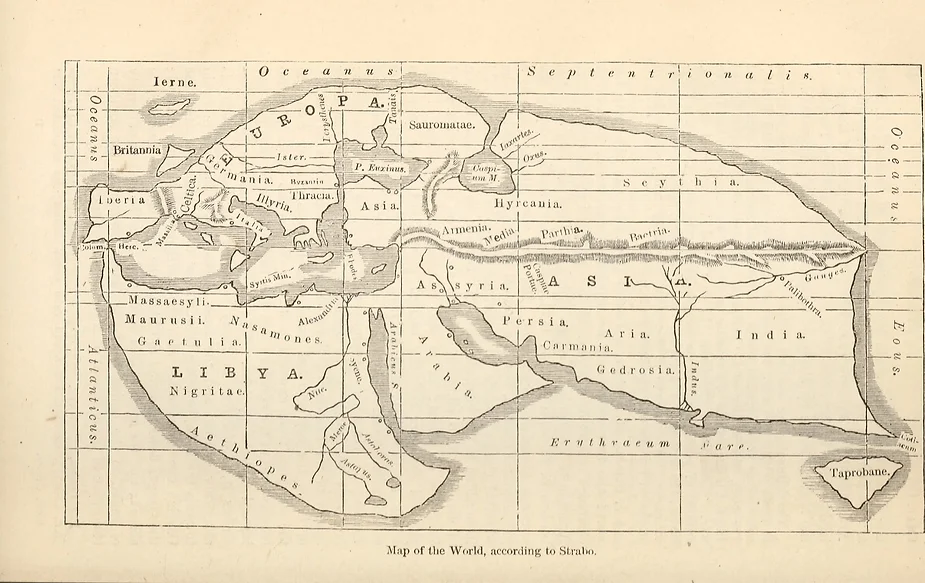

The Roman Empire was an administrative marvel, and its maps, like the famed Strabo one, attempted to present an accurate depiction of the world as it was then understood at the time. Helpful for running an empire, perhaps, but not so good at getting around one!

Map of the world, according to Strabo

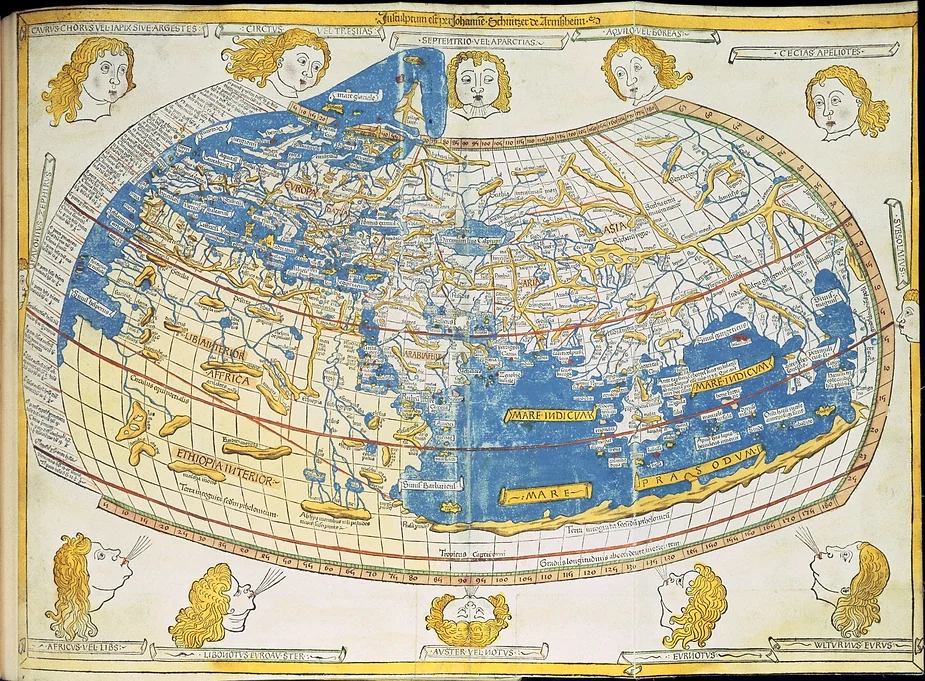

Alexandria, Egypt, 100 CE – Ptolemy created the first map that correctly placed locations in (approximate) relation to each other. He accomplished this through the creation of longitude and latitude, which allows every point on the globe to be accurately described using the two sets of coordinates. Think of it as early geolocation technology!

A 15th-century version of Ptolemy’s map.

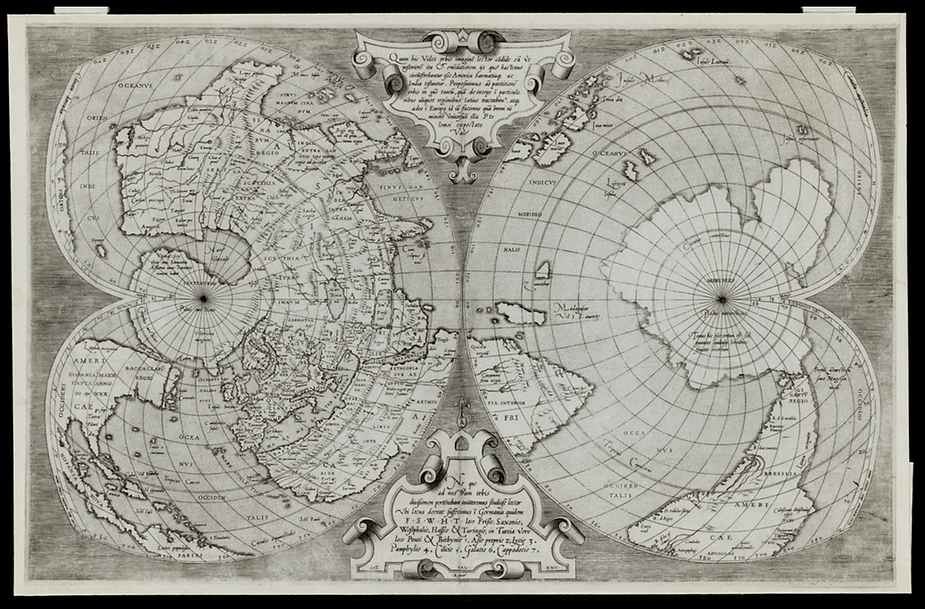

Flanders, 1538 – After Ptolemy’s invention of latitude and longitude, Gerardus Mercator’s eponymous “projections” were the next big thing in mapping. Mercator’s insight allowed a flat map to represent the geometry of a round world.

A 1550 engraving based on Mercator’s work.

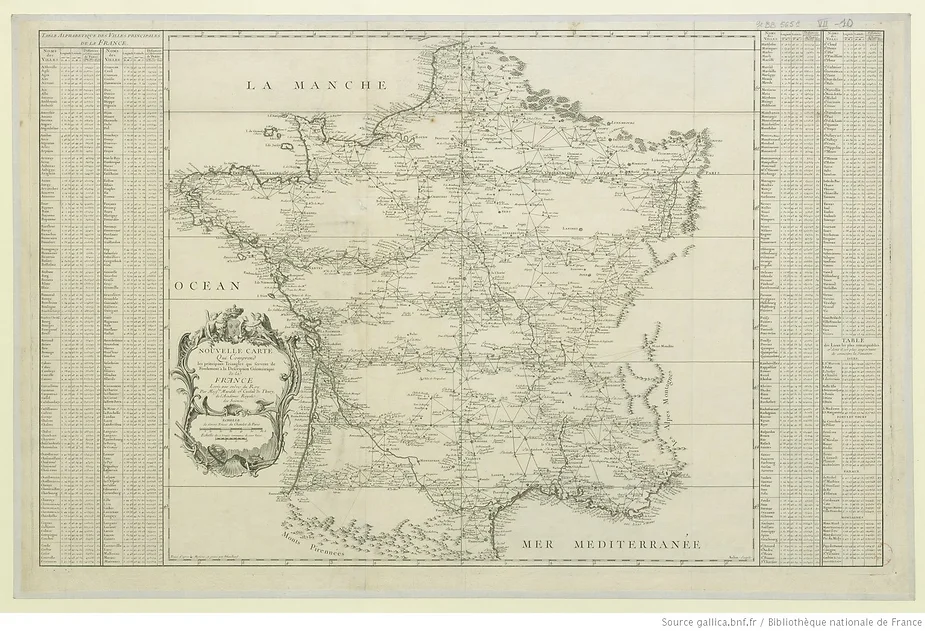

Paris, 1744 – To further increase the accuracy of maps, the Cassini family were the first to use geodesic triangulation to create a precise representation of space – in this case, France. Hey, is that an outdoor cafe I see there?

Cassini’s 1744 map of France.

Koblenz, 1832 – While guidebooks had been popular for many years by the early 19th Century, Karl Baedeker improved the model by providing content and context that would be interesting and helpful for people using his firm’s guides. One could say this was the birth of today’s digital points of interest (POI) technology!

At each step along the way, maps carried more and more detail and information. This progression was carried to the point of absurdity by Argentine author Jorge Luis Borges. His collection of stories, The Maker, first published in 1960 includes a short excerpt, purportedly from a larger imaginary work, titled “On Exactitude in Science.” It describes a “cartographers guild” that created a map as large and detailed as the space it seeks to present – even when that space is as large as an empire. The result is a meta-map, if you will, combining the real and the imagined in one space.

Detail from page 674 of “Paris and environs, with routes from London to Paris. (1913)

Spatial Computing for Navigation

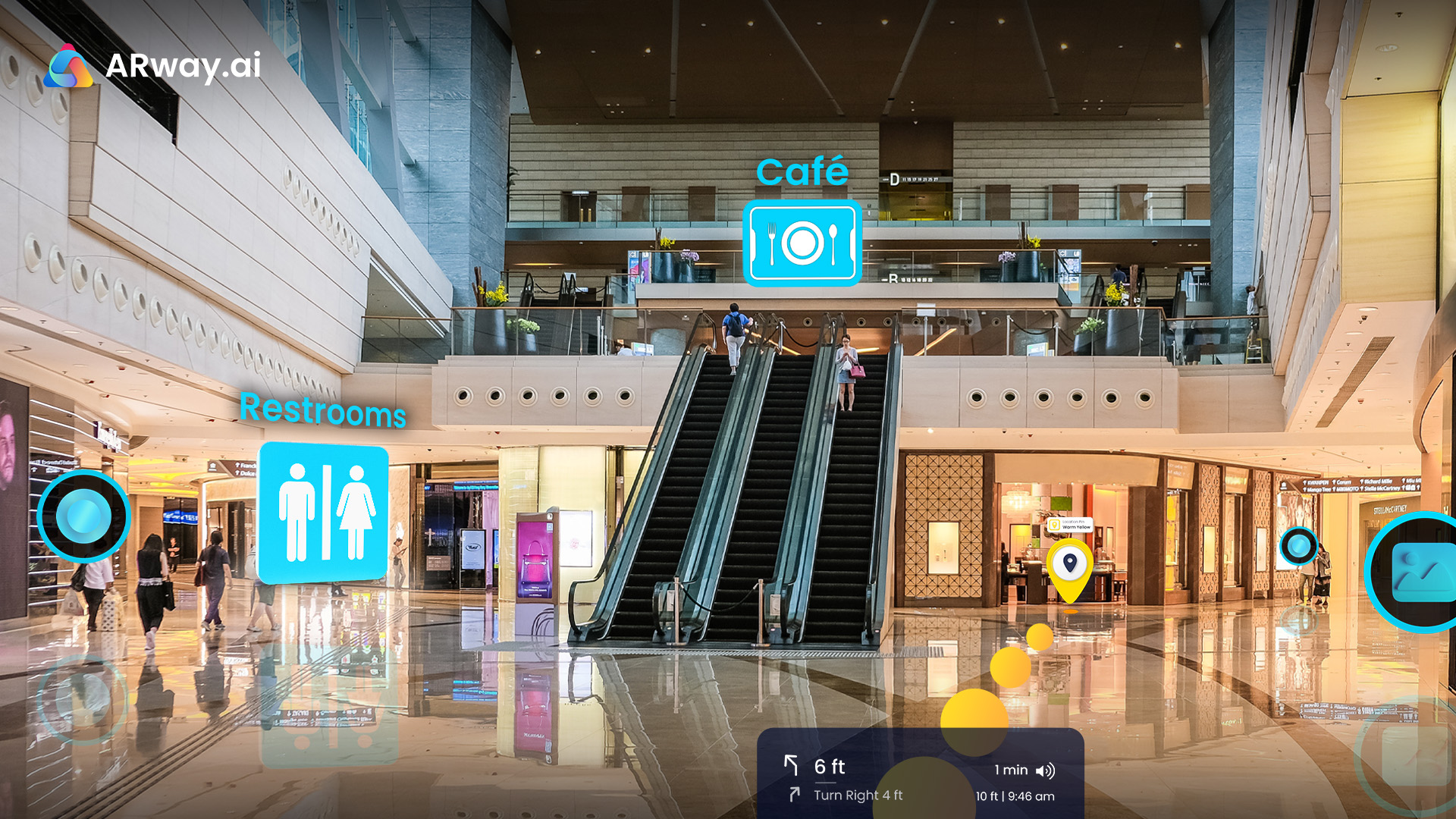

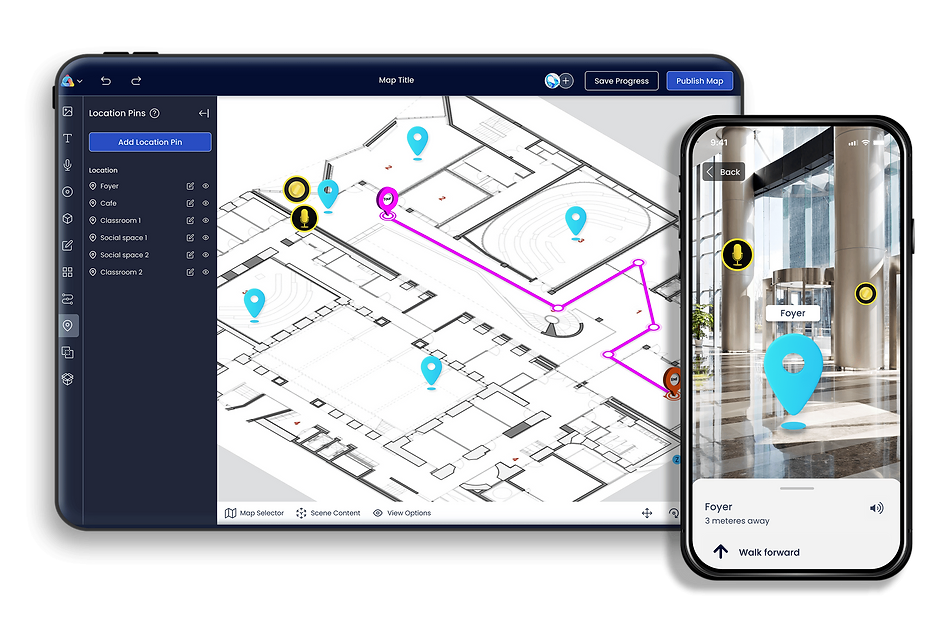

Perhaps it’s not so absurd after all. In some ways, this is what we do with ARway, our real-world Metaverse spatial mapping platform. We apply proven – and emerging – spatial computing technologies to enable advanced wayfinding and navigation capabilities. These allow ARway customers to enhance real-world locations at scale with interactive content, customized routing, audio, images, holograms, and more. For map users, the experience is like peering through a magic window, where the world can still be seen but where it has been enriched in new and wonderful ways.

To the left: ARway creator portal with an AR-populated floorplan. To the right: ARway app showcasing the map in use.

The applications for this technology – like the utility of maps themselves – are boundless. From wayfinding and navigation to augmenting advertising with contextual information that helps shoppers find exactly what they are looking for, ARway melds the real with the virtual and connects both to place. If you’re interested in stepping into the visionary maps of today, contact us here.

Attribution

¹ “The Babylonian map of the world Late Babylonian, 700—500 BC” by Haluk Ermis is

used under CC BY 2.0.

² “Map of the World, according to Strabo” is in the public domain.

³ “Beatissimo Patri Paulo Secundo Pontifici Maximo. Donis Nicolaus Germanus” a 15th

century version of Ptolemy’s map is in the public domain.

⁴ “Quam hic vides orbis imagine[m] lector ca[n]dide ea[m] ut posteriore[m] ita & eme[n]datiorem ijs que[…]” a 1550 engraving based on Mercator’s work. The image is used under CC BY 2.0.

⁵ “Nouvelle carte qui comprend les principaux triangles qui servent de fondement à la Description géométrique de la France. Levée par ordre du Roy par Messrs. Maraldi et Cassini de Thury, de l’Académie royale des Sciences. / Tracé d’après les mesures et gravé par Dheulland ; Aubin scripsi” Cassini’s 1744 map of France. In the public domain.

⁶ Detail from page 674 of “Paris and environs, with routes from London to Paris : handbook for travellers” showing not only streets, but also places of interest. In the public domain.